German researchers discovered in Turkey the earliest megalithic ritual architecture, including preserved human skulls with artificial modifications. They found three partially preserved skulls whose carvings do not seem to align with any previous finding.

The site is called Göbekli Tepe, and it sits on top of a hill in southeastern Turkey. It is at least 4,000 years older than the Egyptian Pyramids.

The evidence found in Göbekli Tepe goes to show that there may have been a skull cult in the Early Neolithic of Anatolia and the Levant, becoming the earliest known to date.

A 9,000-year-old skull worshipping temple

Lead researcher Julia Gresky from the Department of Natural Sciences at the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin explains that human skulls are objects of worship. Our ancestors believed that they could transmit protective or healing properties. In many cases, these beliefs drove primitive civilizations to establish what researchers know as “skull cults.”

There are many types of ancient skull cults spread throughout all continents and cultures. The area of Southeast Anatolia and the Levant, which is where Göbekli Tepe resides, now joins the group of sites with skull-based architecture.

One of them, located in Turkey as well, is Çayönü Tepesi, where researchers unearthed about 70 skulls in one of the buildings alongside a 1-ton polished stone block serving as an altar. Skulls also act as a base for decorating, painting and remodeling its facial features in a ritualistic fashion.

“At present, it is unknown whether these treatments were performed in the frame of ritual activities in the monumental buildings or were brought to the ritual center from settlement sites within its catchment,” writes Gresky, referring to Göbekli Tepe.

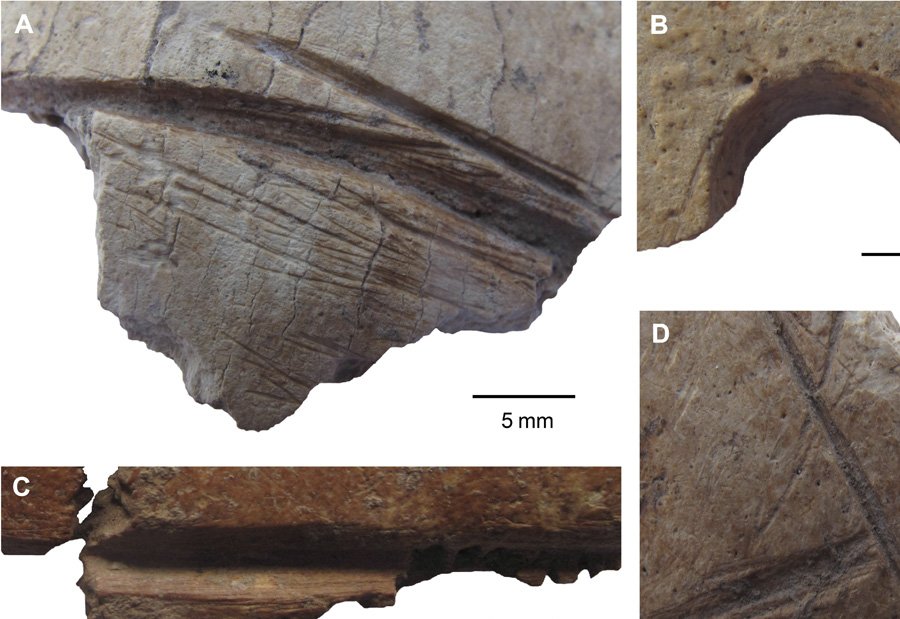

In the case of Göbekli Tepe, researchers found three human skulls with “intentional deep incisions” made on their sagittal axes; one of the skulls also shows a drilled cavity. Researchers recovered a total of 691 human bone fragments at Göbekli Tepe, among which 408 were parts of a human skull.

After analyzing the remains, it seems that the skulls belonged to adults aged between 20 and 50 years of age. Also, one of the skulls shows remains of ochre coloring.

Microscopic analysis revealed that the carvings were made with stone tools and that due to the precision and depth of each cut, it is unlikely that they were incidental. There are also accidental cut marks due to the flint blade slipping from its intended trajectory. Small cuts are also present, which show that the skulls were defleshed and cleaned before they carving.

The carvers cut the skulls when the bone was still elastic, meaning that the ritual took place shortly after the death of the three adults.

One of the cuts stands out from the rest, as it was drilled in rather than carved. The hole is located in such a way that the skull would face forward when hung from a string.

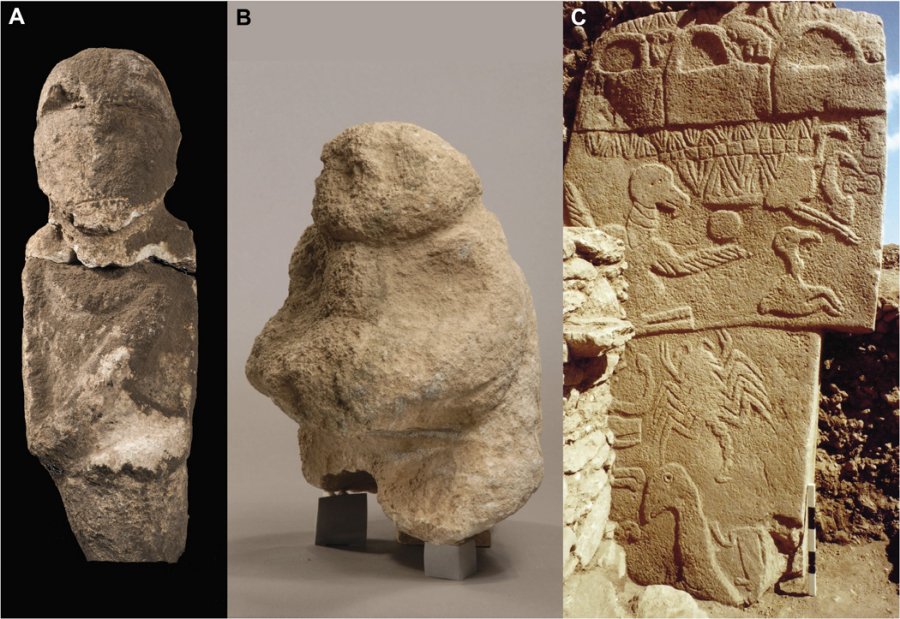

Oddly enough, no traditional burials are present at Göbekli Tepe, although it is clear that human skulls had a special place of worship in its inhabitants. When examining the site at Göbekli Tepe, researchers found huge buildings and T-shaped limestone monoliths, sculptures, and reliefs with unique symbolism, most of it based on worshiping the human skull.

“Skull cults are not uncommon in Anatolia. This was not a settlement area, but mostly monumental structures. We are still in the beginning of working to understand the anthropology of the site. Hopefully we will find some more bones and skull fragments. Then we can get a clearer picture of how these people lived,” stated Gresky.

Researchers concluded that Göbekli Tepe had to be the ritual center of Early Holocene hunter-gatherer groups, yet the reason for carving skulls remains unknown. One theory is that they cut these skulls to brand them, as similar acts in other skull cults depict the act of carving as a postmortal punishment. This conclusion comes from findings in Syria that used skull carvings to humiliate the memory of others. Also, tribes in Pacific and South Asia attached objects to skulls, fixing the mandible in place and using cords to hang them.

“Special status of the individuals could have been emphasized through the application of decorative elements to the crania, which were then displayed (also suspended) at designated points around the site,” reads the study.

Source: Science