Researchers from the University of Michigan (UM), developed a method for the early detection of cancer cells moving through the body, using what appears to be a sponge-like implant to capture them. This method, as reported in the journal Nature Communications, can trap high cell densities and reduce the amount of cancer cells in solid organs by 10 times, giving more chance to the treatments to have positive effects.

The main target for this study is associated with breast cancer, as it is the leading cause of mortality among women because of the difficulty to achieve early detection of metastasis – a concept normally referred to as poor prognosis. The scientists involved in the study argue that metastases are almost constantly detected when it is too late for the organ to keep functioning normally. As a result, when detected, the disease is so advanced that almost any treatment won’t deliver effective outcomes.

However, this advancement in cancer treatments has the potential ability to identify metastatic cells at the early stage, implanting biomaterial scaffolds, to capture and ‘recruit’ sick cells just after the primary therapy is finished. In this way therapies can start while the tumor has not seized major parts of other vulnerable organs.

The test

The test was carried out in mice bodies through the injection of breast cancer cells followed by a tiny scaffold, about 5mm (0.2in) in diameter, implanted in their abdomen fat to see if the cancer cells were attracted to it before spreading to the rest of their organs. The sponge-like biomaterial has been already approved for use in medical devices, as reported by the BBC.

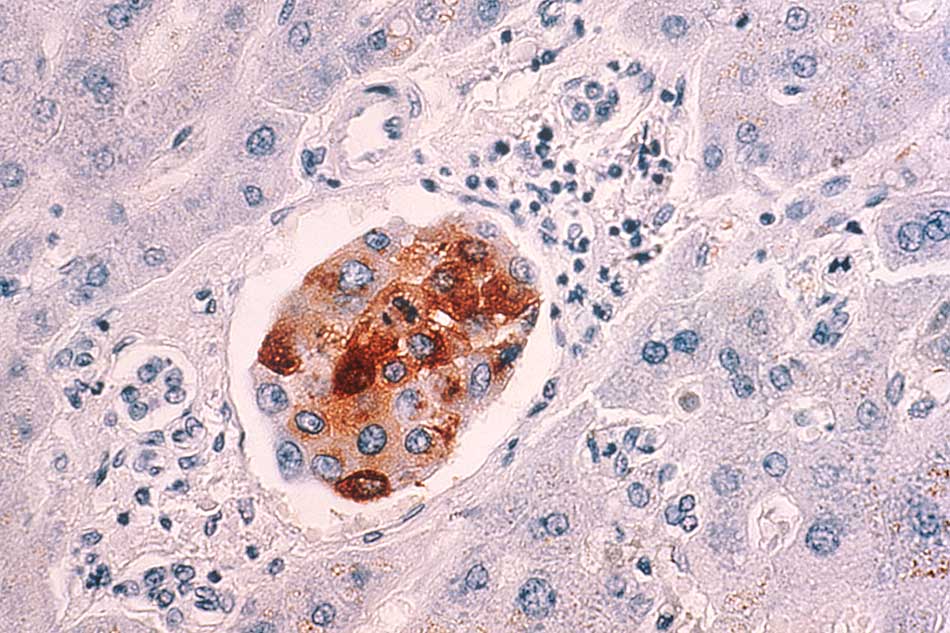

In the study there is a dedicated section to explain the use of immune cells to help this method work. It is titled ‘Immune cells contribute to tumor cell recruitment’, and it explains the critical role of these cells in establishing the ‘pre-metastatic niche’. This concept, as explained in another study by the same journal, refers to a novel thinking that hypothesizes the mechanism in which healthy cells pave the way for future metastasis.

This is why the researchers from UM introduced good cells, so they could prove if Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) were in some way responding to their recruitment mediation. And they did. One of the findings was that immune cells draw the cancer cells to the implant, given that when the sponge gets into the body it triggers an immune response and is colonised by both types of cells.

To finish the test, a special imaging technique that can distinguish between cancerous and normal cells was used and the results were quite astonishing.

The results

The study results showed that the scaffold implant is successful in traping the cancer cells. The examinations inside the laboratory resulted in the lack of presence of cancer cells in the abdominal fat tissue, even in the areas where the implant had not been placed. Moreover, the tumor did not increased its size in the mammary glands of mice as a side effect of the sponge-like implant.

Other organs were positively affected by the reduction of the tumor burden such as the liver and lung. Normally this organs have the tendency to receive the spread of cancer cells from breast cancer. So to speak, the implant reduced the metastatic tumour burden by nearly 88 percent.

Prof Lonnie Shea, from the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan, said that human trials are planned to happen soon enough, “We need to see if metastatic cells will show up in the implant in humans like they did in the mice, and also if it’s a safe procedure and that we can use the same imaging to detect cancer cells,” he said to the BBC.

Prof. Shea, left open the question about the possible outcomes of detecting cancer spread at a very early stage, because it is still a very opaque issue that scientists not yet fully understand.

Source: Nature