Writing down the things that cause anxiety can help to alleviate stress and concerns, according to a new study carried out by the Michigan State University. Through this study, the first neural evidence of expressive writing has been shown.

People worry a lot on a daily basis, which leads to stress, anxiety and related disorders and diseases. Most of the concerns are based on feelings or future events that might never happen. Sadly, it appears to be a condition that many people can’t avoid suffering. However, this new research shows that there are simple things people can do to stop worrying. It backs up the research developed by James Pennebaker in the 80’s about the benefits of journaling to reduce pressure and improve our immune system.

“Worrying takes up cognitive resources; it’s kind of like people who struggle with worry are constantly multitasking – they are doing one task and trying to monitor and suppress their worries at the same time. Our findings show that if you get these worries out of your head through expressive writing, those cognitive resources are freed up to work toward the task you’re completing and you become more efficient” said lead author of the study, Hans Schroder, who is also an MSU doctoral student in psychology and a clinical intern at Harvard Medical School’s McLean Hospital.

What does the field of psychoneuroimmunology study?

In 1986, James Pennebaker, author of Writing to Heal, develop a study about the impacts of expressive writing on our emotional health and the immune system. He asked some test subjects to write about the worst things that had ever happened to them for about 15 minutes. He also asked a group of participants to write about the most mundane and irrelevant things such as the weather. He observed these two groups for six months, and he concluded that the first group had to go fewer times to the doctor compared to the group that wrote about unimportant matters. Thanks to these observations, the field of “psychoneuroimmunology” was created to find out how expressive writing improves the immune system. Pennebaker also stated that people can understand their experiences more if they write them down.

“Emotional upheavals touch every part of our lives. You don’t just lose a job, you don’t just get divorced. These things affect all aspects of who we are — our financial situation, our relationships with others, our views of ourselves . . . [and] writing helps us focus and organize the experience” said Pennebaker.

Based on that, the Michigan State University started this new study to prove the reaction of our brains to expressive writing. This study was funded by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

Expressive writing makes the mind work less

Schroder studied college students who were identified as chronically anxious. They had to fill a computer-based “flanker task” that tested their response accuracy and reaction times. Half of these college students had eight minutes to write about their deepest thoughts and feelings about the task, before completing it. The rest of them had to write about what they did the day before.

While completing the flanker task, researchers measured participants with electroencephalography or EEG. The researchers noticed that both groups had kind of the same level of speed and accuracy on the computer-based test, but the expressive writing group was more efficient as they used less of the brain resources. The study concluded that those who identified themselves as “worriers” can use this technique for stressful tasks in the future.

“Expressive writing makes the mind work less hard on upcoming stressful tasks, which is what worriers often get “burned out” over, their worried minds working harder and hotter,” said Jason Moser, an associate professor of psychology and director of MSU’s Clinical Psychophysiology Lab. “This technique takes the edge off their brains so they can perform the task with a ‘cooler head.’ ” said Tim Moran, a Spartan graduate who’s now a research scientist at Emory University. Both of them worked on this study.

Five minutes of expressive writing a day can help release unnecessary stress

According to this study, practicing being vulnerable with others and with ourselves makes people more aware. Bottling up fears and feelings only makes them occupy our bodies and minds. Therefore, 5 minutes of expressive writing a day can liberate all the forthcoming stress people is carrying within unnecessarily.

That way, people can be able to perform tasks more efficiently. Previous research has also shown the good impacts of writing to our emotional state and to overcome traumatic situations. However, this is the first one to show the neural responses to expressive writing. This research was published online in the journal Psychophysiology.

Source: Collective Evolution

“Thanks to these observations, the field of “psychoneuroimmunology” was created to find out how expressive writing improves the immune system.” This quoted sentence claiming a causal relationship between a desire to understand how expressive writing affects the immune system and the creation of the field of psychoneuroimmunology is wrong on many levels. For those interested in the accurate history of this field, read Ader, R, 2,000. On the development of psychoneuroimmunology. European Journal of Pharmacology 405:167–176

“In 1986, James Pennebaker, author of Writing to Heal, develop a study…” I think “developed a study” is what you had in mind.

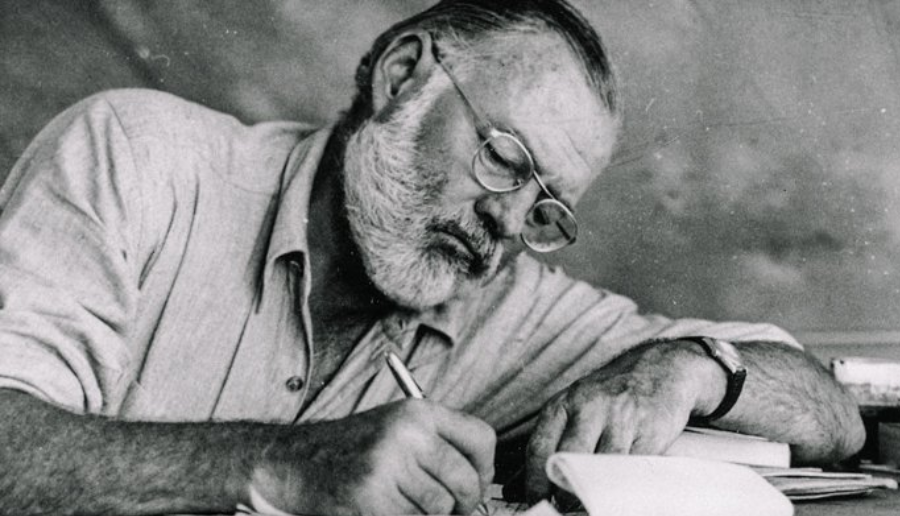

It seems somewhat odd that an article about writing as a method of reducing anxiety would feature a photograph of Ernest Hemingway, who took his own life at the peak of his career. Of course death was a prominent component of Hemingway’s work and often central to his narrative. Hemingway lived and died as he would have had a principal character live and die.

How much sooner would Hemingway have killed himself if he hadn’t written?

And would that have been a bad thing?

Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.

Ernie sobers up a couple years, Voila!, no suicidality. And, Voila!, better writing.

I have written for years and it does help. Depends on your background. But, understand that it can also hold you back and be a vice. Get out there and live your life, and don’t worry about writing everything down. It is a balance.

I always thought trolling was therapeutic

I think it can be. Especially when we learn things about ourselves which we would never know without clear and honest feedback from others who are not invested in our well-being or the consequences of their less than admirable feedback.

Writing helps you articulate what concerns you, but for stress relief, better to take a long walk with the dog.

Writing a daily journal will allow others to judge you after death to their own bent!!

Judge not, want not … keep a stiff upper lip & keep your own counsel. Judge not, want not.

Our judgment about another says more about us than anything else.

Writing allows people to express feelings and focus on the reason for their fears. Everyone wants to have someone to talk to. If you write every day, you always have someone to express your feelings to, your journal.

It certainly did Ernst a lot of good; he blew his brains out at 60, and most of the famous writers of history were drunks and neurotics too…write it down and go down in history.

Clearly we are both the same kind of cynics. I thought the same thing of Hemingway. Many suicides leave behind extensive journals about their feelings and doubts. It would be interesting to find the difference between writing that is helpful and writing that is not.

Plenty of people who wore seat belts, but still died too. Does that mean I think seatbelts are useless in saving lives? No.

I’m sorry but I don’t understand your reply here.

Writing is like a seatbelt in that it is a tool that can greatly improve the quality of your life, though it doesn’t work for everyone, some people still die. But if you look at the data, which this article provides, you see that seatbelts, and writing, trend towards being very beneficial for those who use them, even life-saving.

“The Advisor” is using extraordinary cases of writers who took their own lives to insinuate that writing isn’t helpful afterall, which is a weak argument against the data this article provides.